“Be careful out there, it’s very addictive,” warned our hut ranger Grace, as she bade us farewell from Clinton Hut with a twinkle in her eye.

We already knew that, of course. Afterall, this had been our third try at booking the Department of Conservation (DOC) huts on the Milford Track. Armed with learnings from our first two failed attempts, we were finally successful this round. I remember camping in front of my computer, logged into the DOC portal in advance with all the required fields completed beforehand (details like dates and pax numbers). Then, I waited earnestly with my index finger firmly on the mouse, my iPhone alarm set for 9.30am when the bookings would officially open, and clicked the “book” button the moment it rang.

Receiving the email confirmation from DOC was probably the closest feeling I’d ever experienced to winning a lottery. Finally, we would find out whether the Milford Track, once hailed as ‘The Finest Walk in the World’, was worth the hype. Even though we had missed out on this walk two years in a row, we did manage to fall back on the Routeburn Track and Kepler Track, two close contenders often cited as “lovely alternatives” that are “almost as good” or “even better” (depending on your luck with the weather during the trip). Both the Routeburn Track and Kepler Track have contributed to some of our fondest tramping memories, so it’s hard to imagine Milford topping them!

At the very least, the Milford Track begins in style with a 35km boat ride from Te Anau Downs to Glade Wharf, where we would officially start walking. A single-directional, one-way track with boat transport required on both ends, the Milford Track is one of the more logistically challenging Great Walks. The good news is that we were able to book via the DOC portal both the boat rides and also bus transport to bring us back from the end point (Milford Sound) to the trailhead (Te Anau Downs), where we would leave our car in a small parking space over the next four days of our hike.

After about an hour, the boat finally approached Glade Wharf. The boat’s captain called out for us “independent walkers” to disembark first, ahead of the remaining “guided walkers”. We shuffled to the front with our conspicuously larger backpacks, later on realising that our Milford Track experience would be vastly different from theirs.

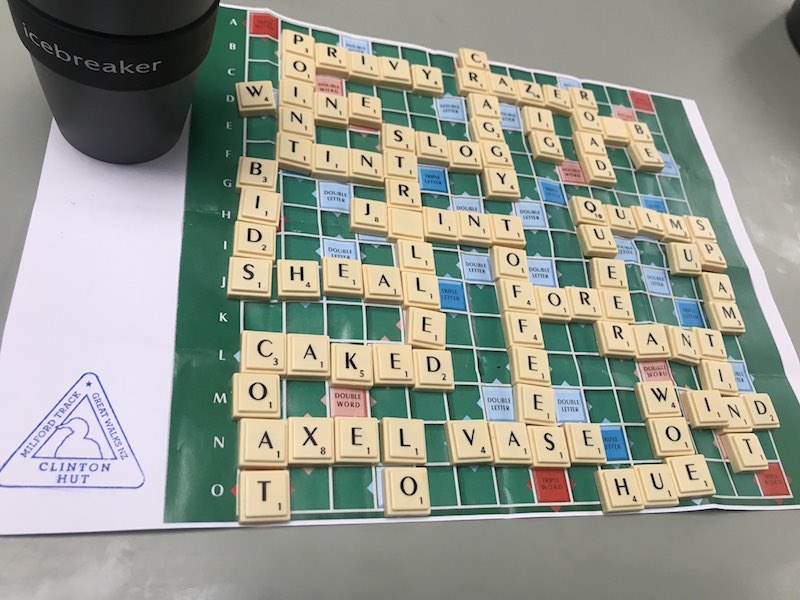

With a price difference of 5-6x, the guided walkers would be tramping in style as they sleep in private lodges complete with comfortable beds, hot showers and three meals a day, including a hot breakfast, prepared lunch and a three-course dinner including beers and wines available for purchase. Not that you can’t pack your own alcohol as a lowly independent walker, of course. We’ve definitely seen our fair share of determined trampers across Great Walks, who have lugged wine along in all forms – from bag-in-boxes to corked bottles.

However, the Milford Track has not always welcomed people from all walks of life. It was first established in 1888 as a private track for the rich, accessible only via commercial guided tours up till as recently as 1965, when a courageous group of Otago Tramping Club members staged a “freedom walk”. The revolution gathered enough public support for the authorities to open it up to the masses, with additional basic huts to be built. This may have even set a precedent for other walks like the Routeburn and Tongariro. Today, a dual quota system continues, with an approximately even split between guided and independent walkers in terms of allocations on the track.

Thanks to the rebellious pioneers, we were making our way through prehistoric rainforests and glacier-carved valleys into the heart of Fiordland. The first day of the Milford Track was the least strenuous, with just a flat 5km walk from Glade Wharf to Clinton Hut, where we would be staying for the night. While not quite the same as the guided walkers’ luxurious Glade House we had passed by earlier, we were perfectly content to be checking into a warm, humble shelter, as we put our bags down and reserved our bunk beds, before heading to the shared kitchen to prepare dinner.

This was our first multi-day trip since embarking on the keto diet, so we were still very much experimenting with camping food. Our new low carb healthy fat dietary preferences meant replacing the usual pasta and energy bars with nuts, butter, nut butter, cheeses, fresh vegetables and canned fish. Even though great walkers are a generally forgiving bunch, we soon realised that heating up canned sardines in the confined kitchen didn’t make us the most popular trampers. So despite sardines being some of the most nutrient-dense options packed with protein and heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids, we made a note to leave them for trips when we can cook them miles away from anyone else.

Luckily for us (and everybody else in the kitchen), the hut ranger came by shortly after dinner to invite us outside for some fresh air with a guided nature walk. We didn’t venture far from the hut, but Grace took us on a journey back in time as she highlighted the wonderful uses of the natural ingredients in her backyard garden.

“This could be useful for our trip,” Kt remarked as he inhaled the fresh lemon scent emitting from the glossy Tarata / Lemonwood leaves crushed between his fingers. In the past, Māori would use these lemony leaves as perfume. Not that we would actually need it of course, given our trusty icebreaker gear, which too harvests the magical ability of nature to keep us odour-free with the antibacterial properties of merino wool fibres, even after days of activity.

Then, we were handed plucked leaves of the Horopito tree, traditionally used by Māori to treat stomach pain and diarrhoea. They had a peppery taste when chewed.

Nobody took up Grace’s offer of moss bunches though. Apparently, these soft and absorbent sponges make excellent toilet papers, and even come naturally infused with iodine, a germ killer. Definitely a tip that could come in handy when answering nature’s emergency calls.

We did, however, happily pick a few stalks from the Mānuka bush right outside our hut after Grace had confirmed we could make tea by steeping its leaves in boiling water. It was the perfect drink to cap off our first night on the Milford Track before the big day tomorrow.

When we left in the morning, the weather was taking a turn for the worse. Besides warning us in jest about the dangerously addictive nature of the trails, Grace had also cautioned us – on a more serious note – that we were in for some wet and wild weather ahead. We set off quickly through the majestic Clinton Valley, as dark clouds rolled in above us – two tiny humans walking in between towering granite peaks on both sides, adorned with ribbons of waterfalls like fine, silky scarves draped over the shoulders of giants.

We covered 16.5km that morning and arrived at Mintaro Hut around noon, just before the heavens opened and poured down. It was a good thing we had managed to start the day early at 7am. But with 200 days of rain a year, Fiordland is one of the wettest places in the world. It was almost inevitable to encounter some rainfall across the four days on the track. The weather forecast ahead was looking to become even worse, with a 100% probability of heavy thunderstorms the next day.

However, the forecast also predicted a chance of the rain clearing later that day. With this sliver of hope, an idea was hatched to grab this window of opportunity and explore ahead of the next day’s route. We knew that day three on the Milford Track, with a steep climb up the dramatic MacKinnon Pass, was supposed to be the most spectacular of all. During bad weather, though, the place would be covered in fog with absolutely no views.

With an abundance of optimism, we quickly refilled our bottles and dropped our large bags at the hut, taking with us only our small day packs to run light up the mountain pass. We arrived on a shrouded ridge and tried to make ourselves comfortable, but the cold and doubt slowly crept in by the minute. At last, over an hour later, the clouds parted. We stood jaw-dropped on the edge of the cliff, as the curtains were drawn to let the soft rays through, revealing imposing peaks and deep valleys we never knew were right in front of us all these while. It was a choreographic masterstroke, performed on a colossal, captivating stage. Mother Nature sure knows how to put up a show.

In the end, the 10km detour that day turned out to be the best stretch out of the entire 54km route. The forecasted storm hit hard the next day, and by the time we got up there for the second time, the entire mountain range had been enveloped in thick fog, never to reveal itself again. Most of the trampers in our group would express later on that the Great Walk had been underwhelming, but the handful amongst us who chose to go the extra mile(s) unanimously agreed that this walk was truly special, bringing back with us a shared understanding of how lucky we were to have caught a glimpse of the much raved about Milford magic.

With the curtains back down on day three, we continued trudging through low visibility in our now completely soaked shoes. As we got whipped by the wild winds, the relentless rain was fast transforming the track into one giant waterfall. Given the deteriorating conditions, our new solo hiker friend from the Netherlands, Myka, decided to stick with us on the trail, a responsible move, because it was risky to be out there alone in such bad weather. We found out that Myka had only signed up for the Milford Track three weeks ago, snagging a coveted spot due to a last minute drop out (after revisiting the web portal several times). So, if you had missed out on booking the huts for the upcoming season, not all hope is lost yet!

The pouring rain turned out to be a blessing in disguise, almost appearing to be another deliberate move by Mother Nature for dramatic effect. Massive waterfalls gushed all around us as we crossed suspended swing bridges over burgeoning rivers. Sutherland Falls, one of the tallest waterfalls in New Zealand, thundered down powerfully as we stood at the bottom, looking up in awe. Yet another riveting performance by Mother Nature.

After a long, blustery day of 20.5km in the rain, we were relieved to finally arrive at Dumpling Hut, our last one on the track. The clothes line was fast filling up. Like everybody else, we were drenched from head to toe. It was pure bliss changing out into dry clothes, as we wrung and hung up every piece of gear, before making ourselves comfortable by the fireplace.

Our shoes were still semi-soggy the next morning, but thankfully it was our last day on the track. The final 18km would be a relatively flat one through the rainforest, dotted with yet more waterfalls and swing bridges along the way. We approached our final destination, Sandfly Point, with slight trepidation, wary of being attacked by the notorious blood suckers having to step into their namesake.

Early Māori legend has it that Milford Sound was so stunning that the goddess Hine-nui-te-pō had to release sandflies to prevent humans from lingering too long. Her strategy seemed to be working. Upon hearing the sound of the incoming water taxi, we swiftly stopped slathering sandfly oil on our exposed skin and sprung into action, hastily packing our belongings for the last time on the track before heading to the wharf to board our boat.

Trampers who make it to the end of the Milford Track are treated to a visual feast on the boat ride from Sandfly Point to Milford Sound, often described as the ‘eighth wonder of the world’. Our water taxi slowly glided on the waters, past striking ice-carved mountains that rise above the ocean, including the mighty Mitre Peak that never fails to take my breath away. Despite having seen it multiple times, I whipped out my iPhone once again to snap that iconic picture-perfect postcard shot, knowing that no camera could quite capture the experience of seeing it upfront in real life.

On a rather anticlimactic note, we arrived at the bustling wharf of Milford Sound and were rudely hit by the overwhelming chaos of modern civilization. Throngs of well-dressed tourists queuing up to collect their tickets for a Milford Sound cruise. Families getting ice-cream for their kids. Hordes of tour buses turning into the driveway to drop off yet more visitors, amongst them our shuttle service, here to bring us back to the start point. This was December 2019. Little did we know that it would be awhile before Milford Sound would experience similar levels of activity again, with horrific floods in February 2020 damaging its roads and huts, even completely wiping out a few swing bridges. And then, we all know what happened in March 2020.

But what did we know, back then? We were just grateful to come out of a spectacular hike unscathed, save for a few sandfly bites and soggy blisters. And thankfully – unlike our predecessors who had to walk back the same way to the start – we were able to return via the tarmac roads in the comfort of our air conditioned bus, a luxury made available from as recent as 1954 when the alpine highway was completed after 24 years. The Homer Tunnel alone took 19 years to complete, a 1.3km-long tunnel that cuts through the granite rock of the Homer Saddle, a mountain dividing Milford Sound and Te Anau. Before that, the only way to access Milford Sound was by boat, air or foot – the latter of which, only by the rich!

Perhaps, this is what makes the Milford Track extra special. Without a shadow of doubt, its raw, natural landscapes are pure magic. But the colourful human stories and impressive engineering feats that accompany the track’s rich history, too, are wondrous acts of wizardry.