The Great Barrier Island adventure begins even before you arrive. Located in the Hauraki Gulf about 100km north-east of Auckland CBD, visitors have two options to get there: a four-and-a-half-hour ferry ride or 35-minute flight from Auckland. Given our limited time on the island (an extended long weekend of four days), we opted for the latter – and were in for a pretty unique experience.

After checking in at Auckland Airport, we skipped the security checks altogether and walked straight to board our Barrier Air flight. The 12-seater Cessna Grand Caravan looked almost like a toy plane on the tarmac beside Jetstar’s Airbus A320 (another single aisle narrow-body airliner). As we strapped on our seatbelts, the co-pilot turned around to welcome everyone, before launching into a safety briefing. Once our plane had made a safe landing on the scenic beachside airstrip at the Great Barrier Aerodrome, the same co-pilot proceeded to unload our luggage onto a cart, wheeling them aside to be collected upon disembarking.

“I’ll be there in five minutes,” a cheerful voice responded on the other end of the phone call.

A minute later, a small 4WD stopped in front of us and the owner-operator of our car hire company stepped out. After manually recording our driver license and credit card details on carbon paper forms, he handed us the car keys, instructing us to leave them in the glove compartment when we were done.

Our bewilderment must have been evident, because he reassured us with a chuckle, “Don’t worry, there’s nowhere to go!”

Even before venturing out of the airport, this was already shaping up to be a special place like no other. Afterall, the Great Barrier Island – or GBI as the locals affectionately call it – is often described as “life in New Zealand many decades back”. Its Māori name, Aotea, means White Cloud and almost feels like an early prototype of Aotearoa, the Māori name for New Zealand, which translates to The Land of the Long White Cloud.

Done with the admin, we set off on Aotea’s winding roads, hugging hillsides with periodic clearings that opened up to vast ocean views. In the background, laid back reggae tunes played from the stereo system. The car’s default radio station had been set to the local Aotea FM, perfectly complementing the island’s chill vibes. Just when we thought the world around us couldn’t feel any more surreal, every passing car from the opposite direction started greeting us. Most gave the casual flick of the index finger as they held onto the steering wheel, but we actually received one full rainbow wave sticking out from a driver’s window!

After the string of warm welcomes from GBI locals, we arrived at the end of the main road in Tryphena, one of the island’s main towns. According to our airbnb host’s instructions, we would then need to continue on the gravel road before turning into an even narrower track that looked more like a hiking path. The car rattled violently as we navigated the bumpy road with hesitation, so it was a relief when we approached a gate. We continued onto a tree lined driveway, finally arriving at a wooden house surrounded by bright, blooming flowers and fruiting trees.

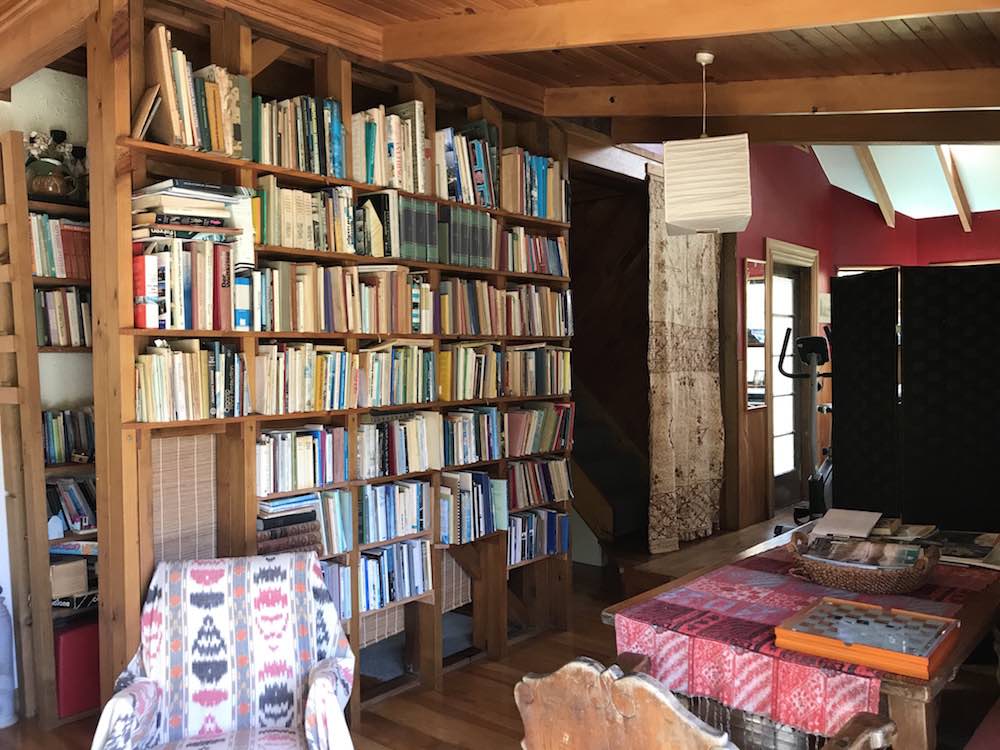

Our hosts, Peter and Helga, have been living here for over thirty years. Originally from Germany and Switzerland, they decided to make this secluded piece of paradise home after falling in love with it. It was easy to see why. As we walked around their spacious compound, the surrounding native forest was alive with birdsong. There was a thriving veggie garden, brimming with lush lettuce, silverbeets, courgettes, strawberries and more. Clearly, they had put their hearts and souls into the land.

Like many others, we had recently dabbled with growing edibles in 2020 – a common offshoot of lockdown boredom – and in the process, cultivated a newfound appreciation for the art and science of gardening. Encouraged by our genuine curiosity (or perhaps alarmed by our greenness), Peter put his rake aside and gave us a tour of his beloved garden. He spoke passionately about nature’s rhythms embodied in the four seasons, explaining that the earth was a single living, breathing organism, one self-sustaining with her own regenerative mechanisms. Pesticides and sprays, therefore, had no place infecting this ecosystem as they disrupt natural healing cycles and destroy long term health.

Later on, Peter would share in detail over dinner his biodynamic approach to pests and weeds.

“I know it sounds crazy, but somehow it works!” he concluded.

The concept of biodynamic farming was not new to us, although I remember having a much harder time concealing my incredulity back when I first heard about it. After all, the idea of filling cow horns with fresh manure and burying it from Autumn to Spring – executed on specific days that align with the cosmic calendar and moon phases – sounds like sorcery. Yet, as consumers increasingly seek chemical-free food produced using organic and sustainable agricultural practices, biodynamic farming has become more commonplace, including amongst reputable Australian and New Zealand vineyards.

That evening, we were introduced to “peppering”, another biodynamic pest control technique that, like the cow horn method, originated from the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner. As Peter explained the process of incinerating the skin of a male rat and scattering its ashes across the land, I couldn’t help but wonder about the so-called science behind it. Perhaps live rats had their own animalistic instincts to detect the death and destruction of their own kind in the soil, and were repelled by it. Who knows? The universe works in mysterious ways, and while we sometimes figure out the way things work through centuries of trial and error, we may never fully understand why they do.

It was only our first night here, but already I felt like my perspectives had expanded multifold. As we retired to our rooms for the night, I paused and looked up. The Milky Way spanned strikingly across a glittery sky full of stars. Off-the-grid and away from big city lights, the minimal light pollution in Great Barrier Island had led to its status as an International Dark Sky Sanctuary. Not a bad place to contemplate about the cosmos.

We got up early the next morning, awakened by a cacophony of kaka calls in the surrounding bush. Banded rails, rarely spotted on the mainland, strutted around boldly as the sun slowly warmed up the ground. Here on the island, the birds are safe from stoats and possums, although rats remain a threat. Our hosts had told us they were part of a local community group of volunteers who set traps around the island. After last night’s conversation, I did for a moment consider the rat traps a likely source of ingredient for “peppering”.

After our scrumptious cheese and bacon omelette generously prepared by Helga, we set off for an activity that was more in our depth. The Aotea Track is a spectacular 25-30km loop around GBI’s central mountainous area. Typically completed over three days, we decided instead to pack light and run the whole route in a day. This would be the first long run since we completed our first 100km at the Taupo Ultramarathon two months ago. Enough time, it seemed, had passed for us to feel excited again about pursuing pointless pain on the trails.

As we drove past the same small towns enroute to the trailhead, we were more aware this time of the ubiquitous solar panels on the roofs of every building, big or small – from beachfront motels to country pubs to the local fire station. Our airbnb, too, was powered by the sun (as the whole GBI is off-the-grid, electricity usually comes from solar panels in the day with a back-up generator at night). Whilst mindful not to unnecessarily waste energy, our hosts shared that their lifestyle hadn’t been too different from living somewhere else “plugged in”. They could enjoy hot showers, watch the TV and do laundry with washing machines. Hair dryers, though, seemed to be generally unacceptable on the island. I suppose I could give up blow-dried hair if it meant living more harmoniously with nature, on a more sustainable planet. The prospect was both inspiring and mind blowing.

Finally, we arrived at the carpark at the start of the Windy Canyon Track. Like a drill for all long runs, we slapped on sunblock on our faces and limbs, lathered vaseline between our toes (and, well, high risk areas for abrasion) before slipping into our comfy icebreaker merino socks and lacing up our trusty Altra running shoes. And off we went.

The scenic Palmers Track at the start was my favourite part of the run, so I’m glad to actually experience this part of the trail twice, running in to start on an anti-clockwise loop before exiting the same way. We started with a steep climb on undulating, exposed ridges that revealed sheer rock faces on one side and the brilliant blue waters of the ocean on the other. Then, we arrived at the bottom of a long stairway that led through a narrow canyon to the summit of Hirakimata, or Mount Hobson. By the time we made it to the top, we were gasping for air, simultaneously drinking in the 360° panoramic views from the highest point on the island.

Descending the steps, we couldn’t help but develop even more respect for Peter, who back in our airbnb shared that he had been part of the team that built these wooden steps. They had to carry equipment through deep mud right to the end, levelling the soil before laying the wooden beams, step by step, backtracking towards the start. It was all thanks to these guys that we could explore with ease the well-maintained track through ever changing terrains and vistas!

After 31km and an elevation of 1,915m, we were back at the carpark. In the end, we spent almost 9 hours on the track, crossing swing bridges and streams, passing through beautiful bush, as well as digging deep on long mundane stretches of gravel tracks without much shade.

Needless to say, we spent the next two days limping all over the island, seeking out recovery activities like soaking our sore legs in ocean pools and drinking the deliciously nourishing local beers by Barrier Brew. We even went on yet another 1.5 hour return hike to the Kaitoke hot springs, motivated by the supposed healing properties of geothermal sulphuric waters. Regardless, the mere discovery of a natural spa nestled amongst lush rainforest canopy – and having it all to ourselves – made the wobbly walk worthwhile.

At the end of our four days, we were buzzing with aliveness from the effects of GBI’s restorative powers. As we moved between activities to re-energise our body, reinvigorate our mind and recharge our soul, the underlying magic formula was, in fact, elemental and uncomplicated. Be it an immersive day out on the Aotea Track; a soak in nature’s heated spa pool; nourishing meals prepared with local, biodynamically grown produce; or late night conversations around cultures and the cosmos – they all led to a deeper connection with nature, and in turn, with each other and with ourselves.